- Pulsus bisferiens, also known as biphasic pulse, is an aortic waveform with two peaks per cardiac cycle, a small one followed by a strong and broad one. It is a sign of problems with the aorta, including aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation, as well as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy causing subaortic stenosis.

- Jul 24, 2019 Examination of the jugular venous pulse; Initial evaluation and management of penetrating thoracic trauma in adults; Management of acute aortic dissection; Patient education: Cardiac tamponade (The Basics) Pericardial complications of myocardial infarction; Pericardial disease associated with malignancy.

- Pulsus bisferiens, also known as biphasic pulse, is an aortic waveform with two peaks per cardiac cycle, a small one followed by a strong and broad one. It is a sign of problems with the aorta, including aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation, as well as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy causing subaortic stenosis.

Examination of the jugular venous pulse; Initial evaluation and management of penetrating thoracic trauma in adults; Management of acute aortic dissection; Patient education: Cardiac tamponade (The Basics) Pericardial complications of myocardial infarction; Pericardial disease associated with malignancy.

The internal jugular vein acts as a indirect manometer of right atrial pressure. Therefore jugular venous pressure (JVP) is a indirect measure of pressure in the right atrium. Basically when pressure in the atrium is high the JVP will be raised and when right atrial pressure is low the JVP will drop.

The right internal jugular (IJ) vein is used in JVP measurement; it’s preferred since it is directly in line with the superior vena cava and right atrium. The external jugular (EJ) vein is not commonly used to assess the JVP because it has more valves and an indirect course to the right atrium, but EJ is easier to see than IJ, and JVP measurements from both sites correlate fairly well.

The left-sided jugular veins are also uncommonly used, since they can be inadvertently compressed by other structures and thus be less accurate!

Diagram showing jugular venous system

Features of the Jugular venous pressure

A venous pulse is not usually palpable. Pressing at the base of the vein will make the vein visible as it continues to fill and distend above the point of pressure.

Hepatojugular reflex aids identification of JVP - probably by forcing blood out of the liver into IVC and therefore into the right atrium increasing its pressure. JVP alters with changes in posture.

Difference between Carotid artery pulsations and jugular venous pressure

The mnemonic POLICE describe the distinguishing features of the JVP:

Palpation: The carotid pulse is easy felt but the JVP is not.

Occlusion: Gentle pressure applied above the clavicle will dampen the JVP but will not affect the carotid pulse.

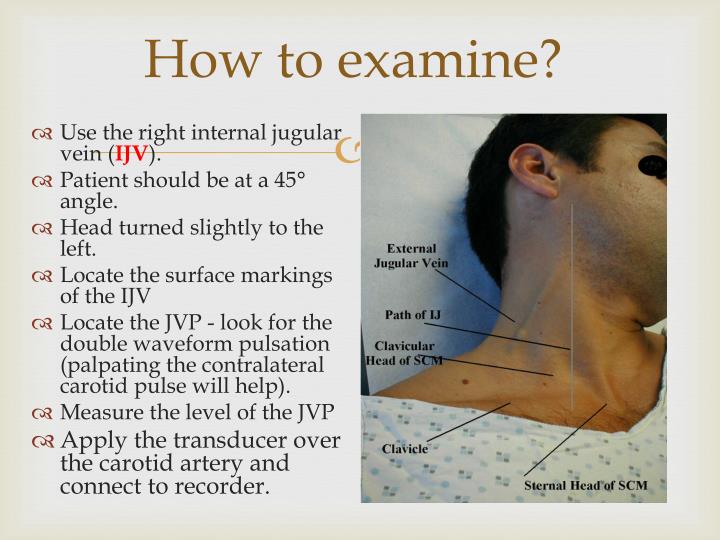

Location: The IJ lies lateral to the common carotid, starting between the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), goes under the SCM, and when it emerges again can be followed up to the angle of the jaw. The EJ is easier to spot because it crosses SCM superficially.

Inspiration: JVP height usually goes down with inspiration (increased venous return) and is at its highest during expiration. (Kussmaul’s Sign describes a paradoxical rise in JVP during inspiration that happens in right-sided heart failure or tamponade).

Jugular Venous Pulse Waves

Contour: The JVP has a biphasic waveform, while carotid pulse only beats once.

Erection/Position: Sitting up erect will drop the meniscus of the JVP while lying supine will increase the filling of the JVP.

How to find the Jugular Venous Pulse

To find jugular venous pressure observe 2 features:

- The height jugular venous pressure, JVP) and

- The waveform of the pulse.

In order to check the height of JVP;

Sit the patient at 45°, with his head turned slightly to the left away from you. (When doing patient examination remember to be on the right side).

You will need good lighting preferably a penlight pointed tangential to the patient’s neck will accentuate the visibility of the veins. and correct positioning of the patient.

Look for the right internal jugular vein (not external jugular vein) as it passes just medial to the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle up behind the angle of the jaw in the direction of the earlobe.

Measure JVP in cm above the sternal notch (angle of Lous) to the upper part of JVP pulsation. Remember it is a vertical and not diagonal distance. Therefore JVP is the vertical height of the pulse above the sternal angle. If it is larger than 4 cm then the jugular venous pressure is raised.

Requires 2 rulers, measure horizontal distance to reference point and then vertical height.

Pressing on the abdomen normally produces a transient rise in the JVP. If the rise persists throughout a 15s compression, it is a positive abdominojugular reflux sign. This sign indicates that there is a right ventricular failure, reflecting the inability to eject the increased venous return.

Identification of the height of the column If JVP is not visible

Pressure too high: elevate the head of the bed to 90 degrees (column should drop with gravity).

Pressure too low: lower the head of the bed (supine).

If you cannot see the JVP at all, lie the patient flat then slowly sit up until the JVP disappears to check the height of the waveform.

Normal JVP 3-4 cm above angle of Louis.

Jugular Venous Pulse Definition

The level of the sternal angle is about 5 cm above the level of mid-right atrium in any position. JVP measured in ANY position in which top of the column is seen easily.

Central venous pressure=jugular venous pressure + 5 cm

Abnormalities of the Jugular Venous Pressure

1) Raised JVP with normal waveform is found in;

- Fluid overload

- Bradycardia

2) Fixed and raised JVP with absent pulsation indicates;

- Superior vena cava obstruction. This is characterized by full dilated jugular veins, no pulsation, oedematous face, and neck.

3) Large a wave indicates;

- Tricuspid valve stenosis - atria contracts against stiff tricuspid and so the pressure in atria rises higher than normal.

- Pulmonary hypertension - there are generally higher pressures on the right side of the heart.

- Pulmonary stenosis.

4) Extra-large a wave known as Cannon wave occurs when atrium contracts against closed tricuspid for example in;

- Complete heart block,

- Atrial flutter,

- Single chamber pacing,

- Nodal rhythm (AV node is in charge),

- ventricular arrhythmias/ectopics.

- Ventricular extra-systole.

5) Absent a wave is seen in atrial fibrillation.

6) Systolic waves = combined c-v waves = big v waves.

These indicate tricuspid regurgitation (c-v wave because the pressure in the right atrium is raised throughout ventricular systole - tip is to watch for earlobe movement!)

7) The slow y descent occurs in tricuspid stenosis (if the HR is so low as to allow the length of descent to be appreciated!)

8) Paradoxical JVP = Kussmaul's sign.

The high plateau of JVP which rises on inspiration. This is known as Kussmaul’s sign with deep x and y descents. Normally the JVP should rise on expiration and fall on inspiration. When the JVP rises on inspiration it indicates;

- Pericardial effusion,

- Pericardial tamponade.

9)Absent JVP.

When lying flat, the jugular vein should be filled. If there is reduced circulatory volume (eg dehydration, hemorrhage) the JVP may be absent.

Jugular Venous Pulse Wave pattern:

The normal JVP consists of 3 ascents or positive waves (a,c and v) and 2 descents or negative waves (x,x’ and y):

- a wave (ascent): Corresponds to right atrial contraction leading to retrograde blood flow into neck veins and ends synchronously with the carotid artery pulse. The peak of the 'a' wave demarcates the end of atrial systole.

- x wave (descent): This follows the 'a' wave and corresponds to atrial relaxation and rapid atrial filling due to low pressure.

- c wave: Due to the impact of the carotid artery adjacent to the jugular vein and retrograde transmission of a positive wave in the right atrium produced by the right ventricular systole and the bulging of the tricuspid valve into the right atrium. This wave corresponds to right ventricular contraction causing the tricuspid valve to bulge towards the right atrium during RV isovolumetric contraction.

- x’ wave (descent): This wave follows the 'c' wave and occurs as a result of the right ventricle pulling the tricuspid valve downward during ventricular systole.

- As stroke volume is ejected, the ventricle takes up less space in the pericardium, allowing a relaxed atrium to enlarge. The x' (x prime) descent can be used as a measure of right ventricle contractility.

- v wave (ascent): due to passive atrial filling (venous filling) when the tricuspid valve is closed and venous pressure increases from venous return – this occurs during and following the carotid pulse.

- y wave (descent): due to opening of the tricuspid valve and subsequent rapid inflow of blood from the right atrium into the right ventricle leading to a sudden fall in right atrial pressure.

Identification of jugular venous waves

The best way to identify the waves (ascents and descents) would be to simultaneously auscultate and observe the wave pattern.

‘a’ ascent: clinically corresponds to S1 (though it actually occurs before S1); sharper and more prominent than ‘v’ wave.

‘x’ descent: follows S1; less prominent than ‘y’ descent.

‘c’ ascent occurs simultaneously with a carotid pulse but never seen normally.

‘v’ ascent: coincides with S2; less prominent than ‘a’ ascent.

‘y’ descent: follows S2; more prominent than ‘x’ ascent.

Moodley's sign

Moodley's sign is used to determine which waveform you are viewing. Feel the radial pulse while simultaneously watching the JVP. The waveform that is seen immediately after the arterial pulsation is felt is the 'v wave' of the JVP

Brian D Hoit, MD

- Professor of Medicine and Physiology and Biophysics

- Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals of Cleveland

Bernard J Gersh, MB, ChB, DPhil, FRCP, MACC

- Editor-in-Chief — Cardiovascular Medicine

- Section Editor — Coronary Heart Disease; Myopericardial Disease

- Professor of Medicine

- Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

James Hoekstra, MD

- Section Editor — Adult Cardiology Emergencies

- Professor and Fredrick Glass Chair

- Wake Forest University

Susan B Yeon, MD, JD, FACC

- Deputy Editor — Cardiovascular Medicine

INTRODUCTION

The normal pericardium is a fibroelastic sac containing a thin layer of fluid that surrounds the heart. When larger amounts of fluid accumulate (pericardial effusion) or when the pericardium becomes scarred and inelastic, one of three pericardial compressive syndromes may occur:

●Cardiac tamponade – Cardiac tamponade, which may be acute or subacute, is characterized by the accumulation of pericardial fluid under pressure. Variants include low pressure (occult) and regional cardiac tamponade.

●Constrictive pericarditis – Constrictive pericarditis is the result of scarring and consequent loss of elasticity of the pericardial sac. Pericardial constriction is typically chronic, but variants include subacute, transient, and occult constriction.

●Effusive-constrictive pericarditis – Effusive-constrictive pericarditis is characterized by underlying constrictive physiology with a coexisting pericardial effusion, usually with cardiac tamponade. Such patients may be mistakenly thought to have only cardiac tamponade; however, elevation of the right atrial and pulmonary wedge pressures after drainage of the pericardial fluid points to the underlying constrictive process.

In both cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis, cardiac filling is impeded by an external force. The normal pericardium can stretch to accommodate physiologic changes in cardiac volume. However, after its reserve volume is exceeded, the pericardium markedly stiffens. An important pathophysiologic feature of both cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis is greatly enhanced ventricular interaction or interdependence, in which the hemodynamics of the left and right heart chambers are directly influenced by each other to a much greater degree than normal.

Subscribers log in here

- Chou TC. Electrocardiography in Clinical Practice: Adults and Pediatrics, 4th ed, WB Saunders, Philadelphia 1996.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline for the clinical application of echocardiography www.acc.org/qualityandscience/clinical/statements.htm (Accessed on August 24, 2006).